|

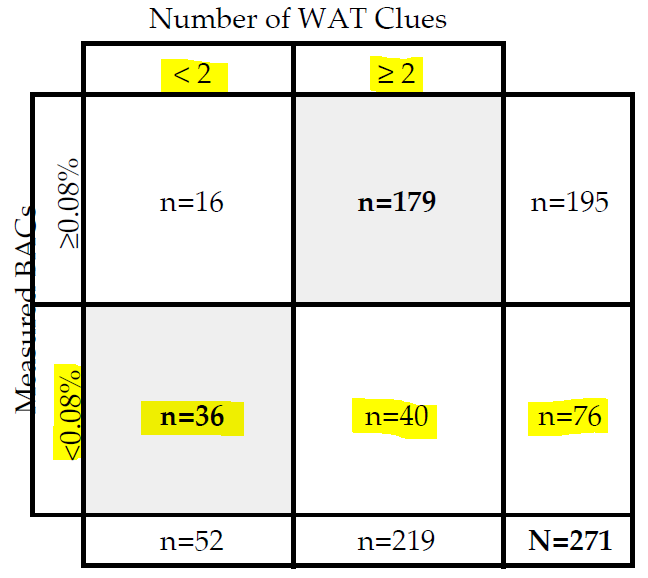

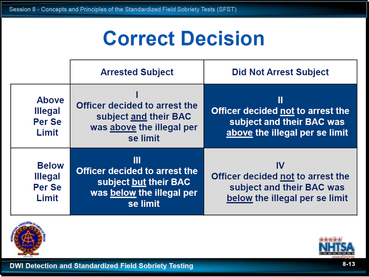

For anyone who has crossed a cop regarding the validation studies, you know that some judges will let you do it and some will cut you off early on. Another way to prevent this is to provide the studies to the witness in advance of the hearing, but this is not without its pitfalls. The studies, especially the abstracts, speak as though the field tests are infallible indicators of BAC and a prosecutor can find their fair share of gems to bring out if they actually read them. I propose a different approach. At a motion to suppress hearing, I often start with the officer on how bloodshot glassy eyes and flushed face are not reliable indicators of DUI from the 1997 study by Jack Stuster entitled The Detection of DWI at BAC’s Below 0.10 using the paragraph on page E-10. I start with that study because I have used it before and the judges and officers are used to hearing about it. If I do it once, we establish that rules of evidence don’t apply at a motion hearing (State v. Edwards, 107 OhioSt.3d 169, 2005-Ohio-6180) and rather than have a big discussion about it, the court concludes that it goes faster to just let me ask my few questions and get it over with. To attack the Walk and Turn test, I use a different study and it works best in cases where the client did relatively well on the One Leg Stand. In that case, I need to focus on the Walk and Turn and try to set up the officer for trial. To do this I can say, “Isn’t it true that most people under the legal limit fail the Walk and Turn?” When the officer says no, I show him the validation study entitled, “Validation of the Standardized Field Sobriety Test Battery at BAC’s Below 0.10 Percent” from San Diego in 1998. This is a good study to use because the manual instructs officers that, "This is the most current research used the describe the accuracy of the SFSTs" (Session 8, Pg. 16) and the instructors of the SFST course are told to "Emphasize this is the study that should be referenced in court whenever possible." (Instructor Guide, Session 8, Pg. 16) In addition, if the officer was trained on the 2009 version of the 2006 manual, the exact matrix was included in their manual in an appendix. Of course, the 2018 manual removed the arrest decision slide, explained below, that followed the same format, but they still instruct officers to reference the San Diego study over all others. With the decision matrix in front of the officer I have him state that 76 people who were under the legal limit were tested and 40 of those 76 failed the test by exhibiting two or more clues on the walk and turn. At that point, the study can be put away. I could continue with the officer at the motion hearing or wait for trial to have the officer confirm that the manual teaches him that tests that are difficult for a sober subject to perform have little or no evidentiary value. (Session 7, Pg. 15) Despite these changes to the manual, at trial, I can ask the officer some of the same set up questions on validation studies and what his training teaches him. Then simply say, “You aware that the study your training tells you to rely on the most demonstrated that most people under the legal limit fail the walk and turn.” If the officer denies it, the transcript from the motion hearing can be used to not only bring out the point about how the Walk and Turn causes sober people to be arrested but also make it look as though he was trying to hide it. If he agrees that most people under the legal limit fail the walk and turn, I can move on to how the manual that states that tests that are difficult for a sober subject to perform have little or no evidentiary value.

Once I have both parts in, I can change the subject entirely and save the rest for closing argument. In closing, I can explain to the jury how the NHTSA Manual, the bible of DUI investigations, tells you that the Walk and Turn test has little no evidentiary value and it is unfair for the State to use it as evidence of DUI when most people fail the test sober.

9 Comments

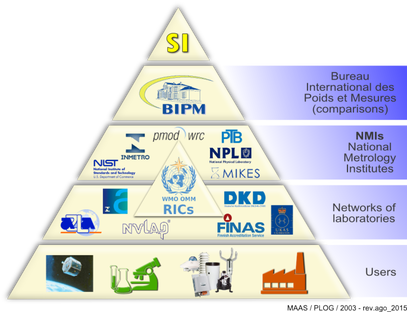

The Ohio Administrative Code establishes the requirements for the breath testing program in Ohio and states clearly what regulations must be followed for breath test to be used as evidence against someone accused of a DUI or other DUI related crime. To get right to the point of this post, OAC 3701-53-04(B) states that “Instruments listed under paragraph (A)(3) of rule 3701-53-02 of the Administrative Code shall automatically perform a dry gas control using a dry gas standard traceable to the national institute of standards and technology (NIST) before and after every subject test.” The machine that this regulation applies to is the highly questionable Intoxilyzer 8000. What makes the machine even more problematic is the State’s decision not to comply with this code section. I am not conceding that the State ever truly complied with this section, but the State certainly does not comply currently. Prior to recent years, the Ohio Department of Health purchased its dry gas supply from ILMO Specialty Gases. ILMO alleged on their Certificate of Analysis that the company used “NIST Standard Reference Material, Certification of NTRM Batch No. XXXXXX, Nominal 210 µmol/mol Ethanol in Nitrogen for ILMO Products Co., Jacksonville, IL” More recently, the ODH has chosen to purchase its dry gas supply from DRYGAZ by CALGAZ. No reason for the switch has been given, but ILMO is still in business and providing the same products. On the DRYGAZ Certificate of Analysis, the supplier does not even claim the gas to be NIST traceable. Instead, the supplier states it uses “N.M.I. Traceable Standards, Certification traceable to National Metrology Institute Traceable Standards.” While they make some reference to NIST with regard to weights, the certification makes clear that it is using “NMI Traceable Standards” on multiple occasions for all analytical purposes. Presumably realizing this to be a problem, the certification attempts to remedy the issue by alleging “NMI is recognized by NIST through the Mutual Recognition Agreement (CIPM MRA).” This statement acknowledges that the alleged entity “NMI” is not NIST. Traceability is a serious topic to scientists and should be a serious topic for lawyers and judges where, as in this scenario, the breath machine creates one of the only actual presumptions of guilt rather than a presumption of innocence in our American legal system. The term “traceability” is a very specific term of art in the science of measurement known as Metrology. NIST has issued policy statements on what it means for a measurement to be “traceable” and the definition is widely accepted and relied upon in many fields. The NIST policy states in part that, NIST adopts for its own use and recommends for use by others the definition of metrological traceability provided in the most recent version of the International Vocabulary of Metrology: "property of a measurement result whereby the result can be related to a reference through a documented unbroken chain of calibrations, each contributing to the measurement uncertainty." (International Vocabulary of Metrology - Basic and General concepts and Associated Terms (VIM), definition 2.41, see Reference [1]). This national policy is crucial to the concept of traceability and to the determination of whether a breath test complies with the Ohio Administrative Code.

It is important for anyone addressing this issue to actually review the CIPM MRA. This document lists each country and its governmental body that acts as the country’s National Metrology Institute. The Certificate of Analysis provided in discovery in the State of Ohio fails to identify which NMI standards the supplier is using and, to be clear, no country’s abbreviation for their National Metrology Institute is actually NMI. It appears as though the ODH is slipping by on purchasing its dry gas cylinders from a new company that does not claim traceability to NIST presumably to save money. Absent evidence to the contrary, it is a reasonable conclusion that a dry gas solution can be more cheaply produced and sold if the components are not strictly traceable to NIST as required by the Ohio Administrative Code.

The 2015 NHTSA manual claims that if an officer observes 4 clues he will be able to classify the subject's BAC as greater than .08 with 88% accuracy. I found this statement troubling because in two recent cases it was relied upon by prosecutors and judges to find 4 clues sufficient to support a correct "arrest decision." So I dove into this issue deeper than the sentence or two reported in the recent NHTSA Manuals.

The NHTSA funded and published HGN Robustness Study of 2007 was the first study to examine this test performed by expert practitioners, under laboratory conditions, and where the BAC was known. This stated that HGN clues are appropriate where the BAC is as follows: < .03 = 0 - 2 Clues .03 - .059 = 2 - 4 Clues > .06 = 4 - 6 Clues In fact, the data from this study shows that 67% of people under the legal limit would be incorrectly arrested by this criteria. While this issue should be clear after being published in a study funded by NHTSA in 2007, NHTSA still stated in the 2013 and 2015 manuals that the presence of 4 clues is 88% conclusive that the subject has a BAC greater than .08. According to NHTSA's own study, however, NHTSA should only state the following: 4 Clues indicates a BAC only greater than a .03 6 Clues indicates a BAC only greater than a .06 Unfortunately, the ramification of such a publication would be that the HGN test would not support an arrest decision at the legal limit of .08. It is true that if you have 100 people and 88 are clearly intoxicated and an officer has at least 4 clues on those 88 subjects alongside an additional 12 people who are objectively sober, then NHTSA can claim an 88% accuracy of the test but it is still bad science based on the data set. All of NHTSA's "validation studies" have traditionally been loaded with intoxicated people. In the San Diego study, the study NHTSA instructs officers to rely on the most, 72% of the people were over the legal limit. This means that even if the officers decided to arrest every single person, the officers would make more correct arrest decisions at a rate of 72% and the tests would appear to be effective. None of the close to 300 people tested in that study had an alcohol level of less than .03, 99.3% had a BAC greater than .04, and 72% were over .08. Chuck Hayes of the IACP who is listed on the Acknowledgements page of the last two NHTSA Manuals presented a webinar on the process and changes that went into the 2013 manual for the Law Enforcement Agencies of the State of Montana. In that webinar, around the 28-minute mark, he spoke regarding the San Diego Study from 1998. He said the following: "And then it was really kind of the very first of the research studies that successfully evaluated the accuracy of the SFST battery identifying BAC levels below .10 and so they identified that the validity of the SFST’s for both .08 and also for .10 but one of the things that that study did, if you read it and read over it well, you will see that it also was helpful in identifying those blood alcohol levels maybe at a .04, .05 in that area. And so for many years, we’ve always said that once you see two clues of nystagmus, so that lack of smooth pursuit and then you see distinct and sustained nystagmus at maximum deviation, well, we’ve said and believed for a long time, because of the research, that that is a good indicator of blood alcohol level at around a .04 - .05. Well the San Diego study validated that for us because that’s what they actually saw in those low blood alcohol levels, so 4 clues now indicates that it could be a blood alcohol level at a .04 - .05 in that area. So the San Diego study helped with that as well and helped clarify that for us." The San Diego study doesn't report the statistics the way Mr. Hayes does, but the Robustness Study supports his position. In the San Diego study, the data was not published, but I assume Mr. Hayes was able to review it. Despite evidence to the contrary, the study puts in its abstract: 2 Clues indicates a BAC > .04 4 Clues indicates a BAC > .08 If the data had been provided, I believe it would not support the statements in the abstract. Take for instance even the title of the San Diego study: "Validation of the SFST Battery at BAC's Below .10" The abstract itself says the average BAC of the subjects tested was .117-.122. It is impossible to validate SFST's below a .10 if the majority of your subjects are over a .10. Despite what the manual states, the available information does not indicate that a subject with 4 or even 6 clues on the HGN has a BAC in excess of .08. |

AuthorAttorney Joseph Hada ArchivesCategories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed